Immunotherapy: A modern era in cancer treatment

By Nitish Bhamidipati

In 2013, the Science Journal named cancer immunotherapy the Breakthrough of the Year

You may be familiar with common cancer treatments: chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation to name a few. Just as a refresher, these therapies are mainly focused on trying to manually remove cancer cell clusters through a targeted approach. While these treatments may be effective in some cases, they often have the side-effect of killing normal cells in the process, making patients weaker and more prone to infection, among other risks. Immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that rather than being centered around killing cancer cells through a toxic flush with chemotherapy, radiation, or some other means, it aims to modify the body’s immune system to better recognize cancer cells and have an overall better trained immune system to fight such cells. Examples of immunotherapy include immune checkpoint inhibitors, T-cell transfer therapy, Monoclonal antibody therapy and more. These are very broad categories and hundreds if not thousands of sub-categories targeting different cancers and cancer subtypes exist.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors work by allowing the immune system to grow stronger than what the body normally allows and thus fight cancer more successfully. Immune checkpoints exist because if the body has a heightened immune system for a long period of time, it risks the development of an autoimmune disorder (Inflammatory Bowel Disease is an example), whereby the body’s immune cells attack its own tissues. However, in the presence of cancer, this stronger immune system is necessary in the short-term, and thus the checkpoints that block the overproduction of immune cells are temporarily blocked.

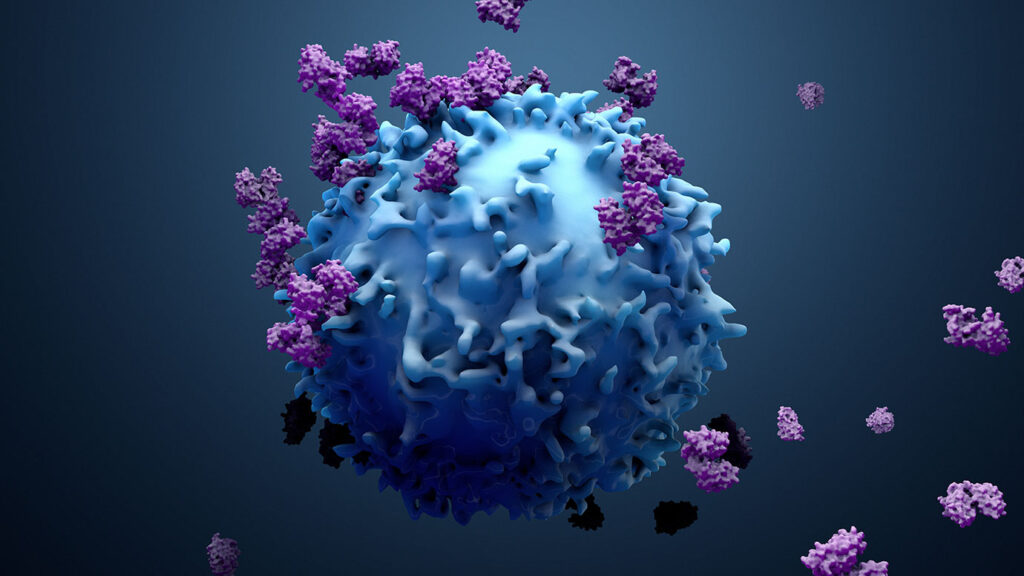

T-cell transfer therapy can be broken up into the subcategories of TIL therapy and CAR T-cell therapy. TIL therapy utilizes T-cells taken from the blood to find out which T-cells are most receptive to the cancer cells that are present in the patient, and then amplify the growth of those cells before injecting them back into the body. In this way, your adaptive immunity has been specifically tailored to fight against the type of cancer in your body. CAR T-cell therapy attaches CAR (chimeric antigen receptors) to T-cells in order to allow the T-cells to better bind to the unique antigens present on the cancer cells and elicit a more effective immune response.

Monoclonal antibodies, which were commonly used during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, are synthetic proteins designed to bind to unique antigens present on cancer cells.

All these methods of cancer treatment utilize immunomodulation (tweaking the body’s immune cells, either by amplifying them, adding receptors to them, etc.) to improve immune responses to cancer.

Immunotherapy is also incredibly powerful because of its ability to be used in combination with traditional cancer treatments. Take chemotherapy like we mentioned earlier. By itself, chemotherapy injects toxic chemicals into the body to destroy tumor cells, taking normal cells that contribute to proper human function with it. By utilizing the principles of immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy, we can attach ligands (things that can bind to cancer cell receptors) on chemotherapy drugs that target specific receptors on tumor cells, almost like a GPS leading the toxic chemicals to the enemy, preserving more normal cells and allowing the patient to remain healthy.

Immunotherapy has been around for a while, but has been gaining immense research interest in the last decade or so. Thousands of researchers are studying the mechanisms behind cancer drugs, trying to discover new pathways by which immunotherapy can become more effective at neutralizing cancer cells. At the same time, we’re learning more and more about individual cancers and their differences. Not every therapy will work the same way for the same cancer, or even sub-cancer (e.g. Triple Negative Breast Cancer being a subtype of breast cancer that lacks specific receptors). If we go one step further, we can see that even the exact same cancer type and the same drug can affect patients differently. Everyday, new research is coming about how new forms of immunotherapy are more effective against certain cancers, and we are building up an immunotherapy bank by which we may be able to match cancers to drugs to maximize effectiveness. The results are promising, but the road to cancer eradication is miles away.

If you are interested in cancer research and want to be on the forefront of human innovation, take action. Reach out to professors in universities near you that are conducting this type of research, and see how you can get involved. It’s never too early to begin research.

Citations: